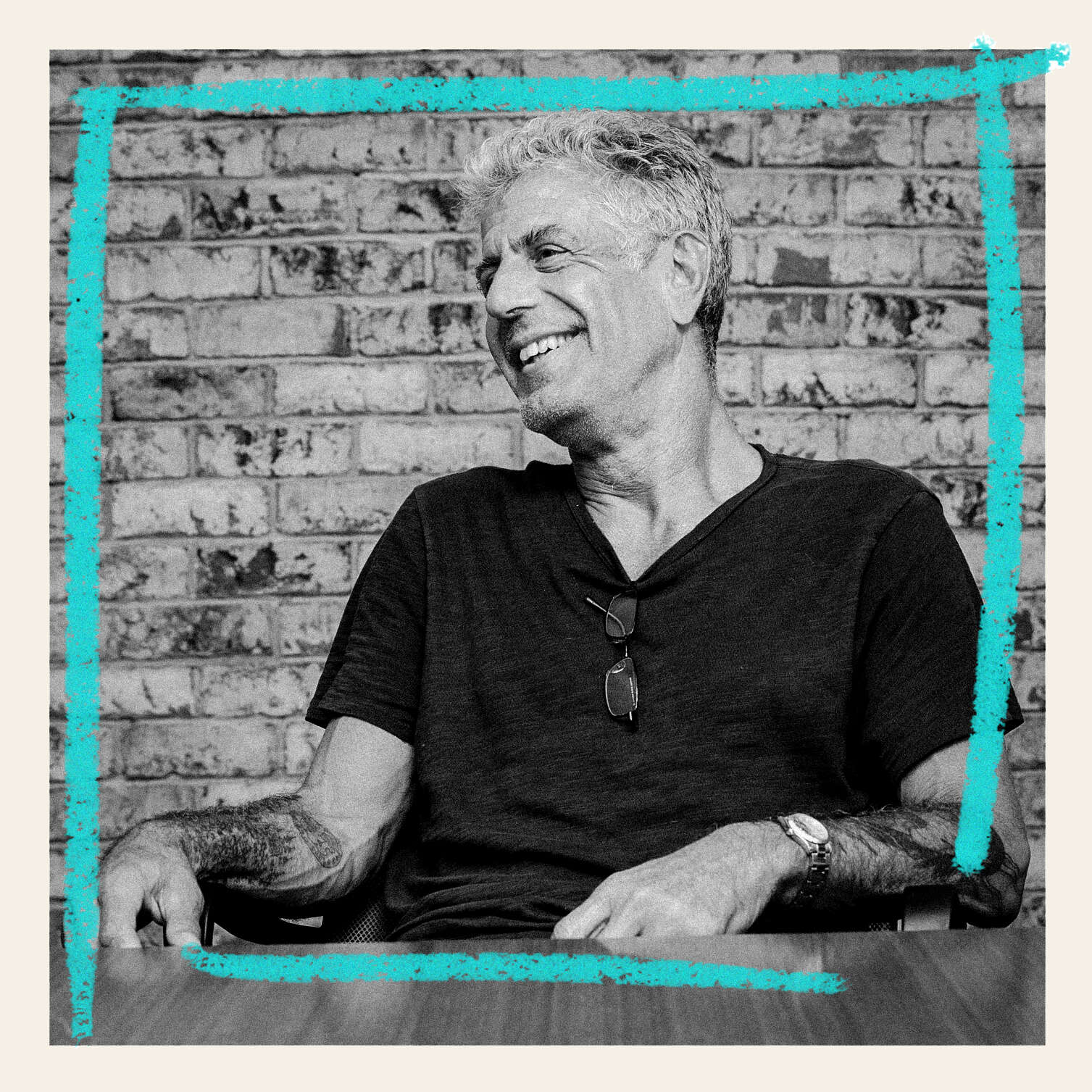

Anthony Bourdain: The Thrillist Interview

The man famously on record about the importance of showing up on time is running 25-30 minutes late. The apologetic text does arrive on time -- with 11 minutes to spare, even -- so I'm giving Anthony Bourdain a pass, especially since the uncharacteristic tardiness directly results in him talking to me for an extra hour.

When he does turn up at the Midtown Manhattan production offices where he puts together Parts Unknown for CNN, he issues a sincere "I'm sorry I was so late" while shaking my hand with a jiu-jitsu-strengthened grip and we quickly get down to business. Nearly 60 minutes later, just as our allotted interview end time, shifted by his delayed arrival, is upon us, a torrential, biblical downpour begins outside, leading to the gifted time. "I ain't leaving anytime soon in that shit, so take all the time you want," he says. "Uber just went to surge rates."

The topics we'd hit prior to the storm included maddening food fads; drug use in kitchens; the no-tipping restaurant trend; beer snobs; and Appetites, his brand new cookbook, filled with recipes (like these three) that he likes to serve and eat at home. But without getting that extra hour, I would never have gotten to talk to him about his obsession with the 1989 Patrick Swayze masterpiece Road House.

First question: What do you know about meat?

Anthony Bourdain: A fair amount. More than I gave the impression I did all those years ago.

I'm alluding, of course, to the hilarious Kitchen Confidential scene about mishearing a prospective employer's inquiry about your meat knowledge as "How much do you know about me?"

Bourdain: Painful is funny, you know? One of the essential rules of comedy is [to mine] the shit that really hurts, your greatest humiliations, the times that we screw up horribly. It's something of a regular feature on Parts Unknown, inadvertently, too -- our biggest failures are often very funny shows. It's not the kind of show I want to make, but my lowliest moments, they're funny, you know?

You ever run into the restaurant owner you were interviewing with again?

Bourdain: I'm not sure if he's around anymore. I've heard from people who were at the interview or certainly worked at what was in fact Bobby Van's, and apparently, I got his brogue wrong, too. I think I identified him as a Scot. In fact, it was Irish. I mean, it was not my finest hour for many reasons.

There are so many cooking and food-travel shows now, which is great in general. But have you found there to be any negative aspects to the rise of reality cooking shows?

Bourdain: I think there is a breed of people coming out of cooking school with TV squarely in their sights, for whom the prospect of cleaning squid for a year in a cellar is unthinkable. This is a problem if you're a chef and looking for a good kitchen staff. But at the same time, you're getting a better-educated group of people, with actual options, entering the business. Whereas before, your pool was sort of, you know, the dumbest kid in the family, the poor people from rural areas. People who had no other option but the service industry. Now you have a lot of people who want to be in the service industry. They've chosen this. If you look at the growth in the sommelier trade, the quality of servers in decent restaurants, I think, has gone up considerably, on balance.

It's easy to make jokes about Emeril [Lagasse], and God knows I did, for many years, but I think on balance, looking back, you have to say that he was a positive factor in the power shift towards chefs. He helped make people give a fuck about who's cooking. Which meant they started to actually care about what they thought they should eat. That's the most important distinction. No one cared before. "The chef feels very proud of this particular--" "I don't give a fuck what the chef thinks -- I want a mixed grill!" was the [response]. You didn't know who the chef was. You certainly didn't want to imagine or picture him. He was a nameless schlub in the back who was there to serve you. When, in fact, he was the first person you should listen to. When you go in a restaurant, who knows better about what's good? What they're good at? What their specialty is? That's useful information.

People are actually interested in hearing those things. For most of my career, setting a menu, 90% of it was, "Well, you have to have this." The conventional wisdom is, for any chance of success, "We have to have, like, a Caesar salad. And a chicken option. We have to have a vegetarian dish. We have to have a steak, probably a sirloin steak. We have to have a salmon." By the time we've finished with all the have-to-haves, the things that you were good at, and believed in, and were passionate about, there wasn't much room left for that. And that's changed. Now, nobody goes to Le Bernardin with, you know, "I feel like a nice piece of flounder." No, you go in because you've heard that Eric Ripert and his team does something really special there, and you want that. You want to take the ride. So I can endure a Guy Fieri if he's part of that process.

Burn. Do you feel like these shows have created a false impression of what it's like to work in a kitchen?

Bourdain: Yeah, sure. But anybody who goes in laboring under the assumption or thinking it's going to be easy or glamorous is going to be very, very quickly dissuaded. They were not going to last. But that was always the case. There are always delusional people who thought it would be a great idea, who decided to "follow their passion." This was always a lethal instinct. Or almost always a lethal instinct. And I think the genuine problem is that there are a lot of cooking schools around the country who, in a predatory way, have contributed to or have essentially knowingly encouraged people who, in good conscience, should not be encouraged, and leading them to believe that, at 35 years old, they will be able to roll out of this third-tier cooking school, saddled with a huge and often punitive debt, and somehow ever get out from under.

I mean, they're not telling them that, if you're 35, you're going to be grandpa in the kitchen. You're going to be, chances are, the oldest person in the kitchen. That it is physically hard, and that you're going to be getting paid shit, if you're lucky, for the first few years. And if you want to be really good, then you will insist upon getting paid shit, because what you should be doing is working for somebody really, really good for as close to nothing as they're willing to give you, in return for the experience. So that's something that I think it would be useful to point out. That if you have a good job, you're 35 years old, and you think it's going to be easy, or that you're going to make a good living, you at least need a realistic picture of what the business is really like before you make a jump or a commitment like that.

I mean, I admire anyone who wants to cook and knowingly enters the field. It's a hard thing. But, you know, look before you leap. Because I've seen that so many times, kids coming out of cooking school and working in my kitchens, and literally two weeks in, you see it. You look behind the line, and you can just see the dream die. This terrible information sinking in, like, "Oh my God, this is nothing like they told me it was going to be."

"This doesn't look like the glamorous stuff I've seen on TV."

Bourdain: What is the god? The true god of the restaurant business, of professional cooking, is not brilliance and creativity. It's consistency. It is doing the same thing, exactly the same, again and again and again. That is the law. Number one. And if that's not attractive to you, then you've really got a problem, or you're going to have a problem.

Right now, the no-tipping trend is in full swing. Do you feel like mainstream adoption of it is going to happen?

Bourdain: I am very, very much for all restaurant people making a living wage. Because as it is now, most restaurant people cannot afford to eat in their own restaurants. It would be laughable. I never had health insurance for almost all of my career.

Crazy.

Bourdain: I never had it. And you know, two weeks' vacation was pretty much unthinkable -- there wouldn't be a job waiting for me when I came back. Holidays off, nuh-uh. Maternity leave, all of those things. I would very much like to see all of that. Is abolishing tipping a positive thing? A way forward? I don't know. I think the fact that Danny Meyer chose to do it is an indicator of what the future is going to be. He tends to be way ahead on these things. I do have friends, however, who provide full benefits, very good salaries, and very good health care who really have a problem with it and say that it is not viable for their system.

Why?

Bourdain: I don't know. I'm just saying not everybody thinks it's a great idea. I don't know if it's the answer. There is a problem; I don't know if this is the answer. But something is needed. I mean, currently, the restaurant business is, generally speaking, not a good living, particularly for cooks. And it's not a healthy workplace for your mental health. I mean, there aren't a lot of 50-year-old chefs still working the line. Where do they go? They're like pigeons. Old pigeons. Where do old pigeons go? Suddenly, they're gone.

There aren't a lot of 50-year-old chefs still working the line. Where do they go? They're like old pigeons. Where do old pigeons go? Suddenly, they're gone.

Americans are pretty cheap, in general. The people who go to a place like Gramercy Tavern know they're going to pay a lot of money to eat. But fine dining attracts a different type of consumer. Won't the average American reject this trend if it takes hold, because they'll see prices going up?

Bourdain: I think, actually, the reverse. The food costs more. It's more and more difficult to even run a fine-dining restaurant. The profit margins are not getting bigger; they will probably get smaller. That space, that part of the market, will probably continue to shrink. People want to move towards casual; more fun, more casual, less demanding, more accessible is only increasing. I think the food that we value, status-wise, is [changing]. You can get just as much bragging rights these days saying, "I found this amazing Sichuan noodle place in the ass-end of Queens. Nobody knows about it. The noodles are $1.29, they're the best fucking noodles you've ever had. Just like in Chengdu." And somebody next to him says, "Well, I just got out of Per Se, and I didn't even have a reservation. I just called ahead, and I just got in. Had 18 fabulous courses, and they comped me, you know, a La Tâche." Who's cooler? That noodle guy! Noodle guy!

Also, look at who's eating at Le Bernardin, for instance. Twenty years ago, it would have been nothing but snowy-haired, well-to-do people, more or less. Now, you go in on some nights -- look around. Sixty percent of the customers are Asian, or Asian-American. Many of them are not particularly wealthy. They're people who can't afford to eat at Le Bernardin regularly, but who saved their money, in much the same way that you save your money to see a band that you love, or to go to a ballgame and get good seats. It is a viable form of entertainment, worth spending real bucks on. What's worse? What is less defensible: to spend $1,000 on Knicks seats, or $300 at Le Bernardin?

Also, I think a lot of the disposable income for people in their 20s -- disposable income that, in my time, would have gone towards, like, cocaine -- is going to restaurants now.

Because they're better informed, right? They're seeing shows like yours and they're like, "Hey, destination food."

Bourdain: Yeah. What finer things to do than travel and eat well? Even if you could only afford to do it rarely, the fact that you aspire to that, and are willing to spend money -- I think that speaks well of people.

That's good. Americans aren't as stupid as we've been told.

Bourdain: We'll see in November.

What do you think is the worst, dumbest, most pointless food trend right now?

Bourdain: Look, generally speaking, I'm surprisingly accepting of these little trends and trendlets as part of a larger, positive process. I mean, I think bogus trends, they don't last long. The restaurant business, in my experience, is sort of like an organic creature. It attacks with antibodies the bogus, the dangerous, the toxic, and drives it out. So that means all of the goofy pretenders who get into the business because they think they're gonna get a TV show. Or the people who do silly food and don't learn from it. Every chef, for instance, does silly food at some point in their career, or food that they maybe shouldn't be doing. But I mean, that's part of the learning process.

So I'm just kind of forgiving of, you know, the ingredient of the month, you know, everybody, "Oh, it's ramps! Ramps! Ramps!" And it's not the worst thing in the world, because 20 years ago, when I started, nobody had heard of ramps. You know, there's a lot of self-seriousness, and pretense, and pomposity, and excess that comes with something that's not that far from show business. But generally speaking -- I mean, the gluten-free thing is ripe for comedy. I tell a joke during my speaking gigs: Celiac disease is a very serious illness, you know? If you think you have celiac disease, shouldn't you see a fucking doctor before you annoy the fuck out of people at a party?

This sort of herd mentality around juice-cleansing. I don't know if that even qualifies as food, but I've had numerous colonoscopies, as most gentlemen of my years have, and you can cleanse completely in about 24 hours. So it's just not something I really understand.

There's a lot that you can make fun of, but is there something egregious, that offends me, that I think must be stopped or crushed for the good of humanity? Eh, not really.

What about 3D-printed food? Have you made any of that?

Bourdain: I haven't, and I'm dubious of it, of course. But I'm an old fuck, so I would be. If you tell me it cooks a hamburger better than a grill, I'm willing to believe it. And I wait for that day. I know of a chef who I like very much, but he was doing edible menus. And, you know, papier-mâché is edible too, technically. I mean, it's not like eating a bowl of fish hooks. But it's not exactly food. It would not be my preferred mouthful, let's put it that way.

OK, so do not invite you to a 3D-printer dinner party.

Bourdain: No, I don't think anyone would be so foolish as to invite me. I'm just not that kind of a guy, you know? I think my tastes, at this point, are pretty well-known. I spent some time with Nathan Myhrvold, who worked with me on my book. I went to his lab in Seattle. And this is a guy who is pushing that sort of experimental, scientific exploration of what can be done with food about as far as you can go. But I will tell you, it was a delicious meal. It was -- much like Ferran Adrià -- it was food first, not "look at me, I'm a genius." For all of the unpleasant imitations of what they did at elBulli, I think it is worth reminding people that, at all times, elBulli was delicious first. It was always specifically referred to as the place to which it belonged; neither Catalonia or his childhood roots in Andalucía. All of the food had shockingly few ingredients. I mean, it wasn't complicated. The techniques were seemingly tortuous, but generally speaking, there were three or four ingredients. And it was always delicious. Almost always delicious. There are people out there, and they are legion, but nobody's eating at their restaurants. Not for long.

Too much of a gimmick?

Bourdain: Yeah. And we went through a period where every place you walk in -- look, it is a fair observation that, no matter what community you go to at this point, chances are there will be a chef with "I Love Bacon" tattooed on his chest, with a charcuterie program. And you know what? The charcuterie might not be that good. But this is clearly a move in a positive direction. There may be a lot of shit charcuterie out there, or maybe it's not there yet, but in a sense, we're becoming more like Italy. You go to agriturismos all around Italy, and they will make their own sausage. This is a good thing, you know? That's how we learn, and that's how we get [better]. We try, and we fail. And we refine. We repeat.

And fads tend to get punished.

Bourdain: Yeah. There's a tendency to over-umami. You know, pork belly with bacon and uni on top, and bone marrow. It's like, dude, I need to drink bleach after this to cut through!

Where do you hope that fast food will be 20 years from now, 25 years from now?

Bourdain: Well, I would like it to look like Singapore. With hawker centers, with independently owned and operated businesses, who have been, for some time, doing the same one or two dishes very, very, very, very well. Selling those things quickly, at an affordable price. That would be good for the world, and I think we deserve it. We have the people for it. We have the clientele for it. I don't understand why we don't have that kind of beloved street-food-type culture that Singapore or Kuala Lumpur or Hong Kong, for instance, have.

So my hope would be that we'd see a lot more of that. And I think, as we become more Asian in character, which I expect that we will continue to become, that those values will become more and more our values. Meaning, people will drive 45 minutes for the right bowl of noodles. And they'll value those noodles in just the same way as a fine-dining experience, maybe even more. That's good.

And then, I think there's room for fast-food establishments that don't suck. That actually give a shit. I mean, Five Guys is a pretty decent fast-food operation. You order a burger there and they cook it for you. In-N-Out is a pretty decent fast-food organization. Shake Shack. These are fast-food operations and it's of decent quality. You get food. You get it efficiently. It's not soul-destroying. You don't leave thinking, Oh, why did I do that? -- filled with self-loathing and despair.

Any despairing moments recently?

Bourdain: Yeah. I mean, the worst ever fast-food meal I've ever had -- I am often guilty of hyperbole, but sometimes, in a vulnerable moment, I will find myself at an airport, hungry, and there'll be no other option but an airport burger. And if it's a bad, carelessly presented burger, where they clearly do not give a fuck, they just can't be bothered, where it's just this ugly machine, and they sling it out, I literally go into a spiral of depression. I doubt the underpinnings of everything. I had a burger at a Johnny Rockets in an airport, and it didn't just ruin my day -- it ruined my week. I thought, What kind of a world do we live in? There's four guys standing here. It's an empty restaurant. And I reach into, like, a shelf and just pull out this pre-cooked burger. They didn't even bother to re-dunk the fries in the grease. It was a sort of utter contempt. Nobody cared.

Now, it's true, they're paid minimum wage, probably, or close to it. An argument is made, when I complain about these things, "Well, you know, if you were getting paid minimum wage, standing in an airport, slinging burgers, you wouldn't give a fuck, either." You know what? Much of my career, I was paid minimum wage, or close to it. I never took home more than $1,000 a week, ever, in my entire career. When I started out, I was clearing $100, if I was lucky. And I gave a fuck. You know, I had a little pride. I tried a little hard. You know, sometimes the company doesn't let you. I get that. And we are seeing, apparently, a lot of these outfits, their market share is shrinking. And that's good. I think fear and contempt of generic fast food is a useful instinct. There's plenty of room -- it's like the independent bookstore versus the massive chain. You know, I root for the good guys. Who wouldn't?

If you could eradicate one chain restaurant from the planet, which one would you pick?

Bourdain: Johnny Rockets. I mean, it's personal.

What is the next In-N-Out Burger?

Bourdain: I have no idea. It has yet to identify itself. It doesn't look like it's gonna be Chipotle, though, does it? They shat the bed.

And they caused people to, as well.

Bourdain: Yeah. What I find interesting is the proliferation of juice joints. These people are selling little bottles of coconut water for like, two and a half bucks. Those smoothies are not cheap. And you know, they're microwaving oatmeal. Big fucking bucks. Because it's "organic." At least people are thinking about what they're putting in their mouths. So, I mean, I guess that's positive.

And I could make fun of hipsters all day long. But you know what? God bless them. Because they're out there making -- I may not want them to call it "artisanal pizza," maybe it grates to hear that, but chances are, it's better pizza than I was eating 20 years ago. And somebody gives a fuck. That's the point. You know, there are hipsters out there making cheese. Who made cheese 20 years ago, 30 years ago?

In a chapter in Appetites about hamburgers, you call out restaurants that serve house-made ketchup.

Bourdain: Yeah, that's just -- I think it's a matter of personal taste. I've never had ketchup better than, you know, the common variety. Plus, that's such a bone-deep flavor profile. Don't fuck with it, you know?

Totally. Thank you.

Bourdain: You put, you know, chipotle aioli on my burger without asking, I would prefer you not. I want fucking ketchup. I discuss this in the book: tomato soup. The Platonic ideal of tomato soup, for me and many others, is what mom made because she opened a can. I don't want it too obtrusively outside of that comfort zone.

It needs to at least remind you of something, right? In an nostalgic way. That's what you want.

Bourdain: Yeah. I think that's what Ferran Adrià did very, very well. No matter how far away he went, it always brought you back to a familiar place.

There's a proliferation of recipe videos that involve mashing up seemingly incongruous foods. Boon or bane?

Bourdain: I'm not about novelty food, if it's just for novelty, or you know, like, state-fair food. As much as I like presidential candidates choking down corn dogs, and deep-fried butter, or whatever else, I don't think it's good for the world, you know? Fuck that. Is it good? That's all I want to know. Is it good? Is it delicious? I'm willing to try anything that is making an earnest attempt to be delicious. I don't need "look at me" food. Who does? Is it better than Krispy Kreme and a decent street slice? Chances are, it's not.

What do you think people get the most wrong about you?

Bourdain: About me? I don't know. I don't feel I've been treated unfairly. But look, in the years immediately following Kitchen Confidential, in spite of the fact that the period of time covered in Kitchen Confidential, those years, had already long gone -- I wasn't doing cocaine, I wasn't fucked up on heroin, I wasn't pounding tequila shots all night, or going out with waitresses -- I would bump into a lot of line cooks on the road who would want to do those things, and would expect me to take part. I don't think that I've suffered from that and, over time, it's something I never took seriously. I didn't feel the need to undermine it, you know, like, "I will prove that I'm a different person now by performing in a tour of King Lear."

Some people are instinctively not going to like me, for very understandable reasons. Others will like me for reasons that I don't particularly identify with or feel are necessarily representative of me. But that's OK. I just don't care. I don't feel any obligation to play a part -- or not play a part, for that matter. I often bring up Hunter Thompson as a sort of cautionary tale here -- a writer who I clearly admired very, very much, but I think somebody who, when he'd show up, people would expect him to be Hunter Thompson, Duke from the book. And he complied. He did. And I don't think that was good for him, or his work.

Success came late to me, so I sort of knew what I wasn't and what didn't make me happy. I'm not saying I know how to be happy, or how to be a good person, or any of those things. But I know the bad things I'm capable of. I know what doesn't work, and didn't work. I know what hurts other people. I know how to disappoint people, hurt them, betray them, let people down, let myself down. I know what it's like to look in the mirror and be disgusted and ashamed. You know, I've tried very hard since that first lucky break to not fuck up.

I know the bad things I'm capable of. I know how to disappoint people, hurt them, betray them, let them down, let myself down. I know what it's like to look in the mirror and be disgusted and ashamed.

The restaurant industry still hasn't cracked down on, or at least still accepts, drug use in the kitchen, yet it's a serious problem. Why hasn't there been more oversight on this?

Bourdain: We're talking independently owned and operated restaurants with a thin, if any, profit margin. Minimal services. To start with, first of all, how do you monitor such a situation. Are you going to piss-test restaurant workers? I mean, where else are they going to work, for god's sake? Alcoholism is probably the number one problem in the restaurant industry. Are we going to crack down on drugs and not alcohol? I mean, a lot of people work in the restaurant business because they're alcoholic.

Ideally, like any other large company, you should be able to go the boss and say, "Look, I have a problem," or the boss noticing you've got problems, says, "Look, we notice you have a problem. You've got a choice. We will happily send you to rehab and hold your job for you, but you need help." But who does that? We are merciless in our hypocrisy and our denial, particularly as far as synthroid opiates right now. I haven't seen a lot of cocaine in the industry in quite some time. God knows, it was central to my life for much of my career. But by the last years, if I saw someone doing coke in my kitchen, I would, in my mind, identify them as a problem. This was somebody who was going to disappoint me. Maybe not today. Maybe they're holding their shit together now, but sooner or later, they were gonna steal, or they were gonna not show up. This was not something I was going to tolerate.

I would not knowingly -- I can think of one exception -- but I did not knowingly hire people with substance abuse problems. And had I discovered one working for me, who needed help, I don't know what my options -- I don't know what I could have offered them, other than a general commitment to hire them back when they got their shit straightened out. If I could. I can't think of a company I worked for that was big enough, with the kind of human resources situation, which I always had problems with -- I don't know. I don't think the systems are in place, and I don't know that the systems are that good.

There's a newspaper in town that -- I believe you have to have a urine test to work at the New York Times. That's fucked up, in my view. I don't expect moral rectitude of cooks. I expect them to hold their shit together. I would like to be able to help them when they need help, just as I would like to help anyone -- particularly as it relates to drugs. I think society as a whole needs to address this. Look, we allowed this massive spread of prescription drugs. Societally, we created millions of junkies, and then we cut off their supply. What did we expect to happen?

I'm very much in favor of taking onus away from people who have drug problems, seeing it as treating it as a health problem, removing the criminal element. This is problematic when it comes to crack, I grant you, because it affects people beyond belief. But I think if you're addicted to opiates, society should be happy to help you. It's much more cost-effective than what it's going to cost them down the line. But I don't expect a guy who runs a small trattoria down the street to be able to responsibly look after his flock.

What effect would mandatory oversight have on the industry?

Bourdain: Who's good at that? Who can be trusted to do that? The police? No. The DEA? No. I've never met a Human Resources department that I didn't have utter contempt for. So I don't know. I wish I had an answer to that. I would like to see a situation where I could go to a cook, or an employer could go to a cook, and say, "Look, you're fucked up. You need help. There's a place down the street, they help people like you. It's right down the street. It's not going to cost you anything. Or, maybe it's going to cost a little, and I'll help." That place doesn't really exist right now. Your options are not good.

A cultural shift within the industry probably needs to happen, too, right?

Bourdain: I don't know. I don't see a lot of drugs in restaurants the way I used to. Snorting a rail off your cutting board at the end of the shift in front of your coworkers would not be OK at any good restaurant in New York that I know of.

You could do that in the '80s?

Bourdain: [Makes snorting sound] Yeah, you'd buy it from the chef or the bartender. Now, no. Just, not. Everyone else is like, "Look, we're working hard here. Try to maintain a consistent situation. You're imperiling all of that."

In Kitchen Confidential, you talked about "failing restaurant syndrome," and the signs that indicate that a restaurant might want to give it up. Do you still look for that when you eat out?

Bourdain: No, now that I'm not in the business anymore, I really try hard to not notice stuff like that. I try to not ever think about food in an analytical or critical way when I'm out eating. I want to experience it totally emotionally. I want to forget where I am. I want to be completely oblivious to the bell in the kitchen. I don't want to notice that the busboys are all clustered together in the bus area, gossiping, or checking their Grindr profiles. I don't want to be aware of that. And if those things intrude, if I'm forced to, that makes me unhappy. I don't want to be analyzing the food: "This is slightly salty, but impudent." I don't want to think like that.

One of the warning signs you mentioned was the bathroom situation.

Bourdain: Yeah, that was before I traveled. Most of the really great meals I've had in my life over the last 15 years have probably had thoroughly filthy bathrooms. Let's face it. If there's like chickens running around the floor of the restaurant, they're feeling pretty confident about the food. They're not insecure about their meal. So many restaurants I've been to in France, for instance, and Italy, you know, there's a cat. Or little dogs running around. That says, "Hey, our food's good. You don't like it, fuck off."

There's a picture of you in the book where you're posing with street food while sitting on a toilet.

Bourdain: Right. The sausage and pepper hero.

That's an awesome shot in the book. It's really funny. And it totally makes sense. It also made me wonder: What's your feeling about actually eating while on the toilet?

Bourdain: Well, I'm against it. But I was trying to indicate that I'm willing to pay the price for a sausage and pepper hero. All roads inevitably lead to that toilet sooner, probably, than later. But not simultaneously. That would be wrong. I've never done that, I hasten to say. President Johnson would give press conferences and talk to the White House press corps while taking a dump. Man, those were different times. No, it's just unthinkable. Even eating in bed -- the commingling food and other bodily functions is not something I'm into. I believe in separation of church and state.

I will refrain from making a "don't shit where you eat" joke.

Bourdain: The short answer is no. Never. I mean, even dogs don't do that. Well, some dogs.

I read somewhere that, based on some drinking on the show, you were getting flamed online from beer snobs. Does that happen often?

Bourdain: A lot. I would say that the angriest critiques I get from people about shows are when I'm drinking whatever convenient cold beer is available in a particular place, and not drinking the best beer out there. You know, I haven't made the effort to walk down the street 10 blocks to the microbrewery where they're making some fucking Mumford and Sons IPA. People get all bent about it. But look, I like cold beer. And I like to have a good time. I don't like to talk about beer, honestly. I don't like to talk about wine. I like to drink beer. If you bring me a really good one, a good craft beer, I will enjoy it, and say so. But I'm not gonna analyze it.

I was in San Francisco, and I was desperate for beer, and I walked into this place. I thought it was an old bar. And I sat down, and I looked up, and I noticed there was a wide selection of beers I'd never heard of. Which is fine. OK, I'm in some sort of brew pub. What's good? But I looked around: the entire place was filled with people sitting there with five small glasses in front of them, filled with different beers, taking notes. This is not a bar. This is fucking Invasion of the Body Snatchers. This is wrong. This is not what a bar is about. A bar is to go to get a little bit buzzed, and pleasantly derange the senses, and have a good time, and interact with other people, or make bad decisions, or feel bad about your life. It's not to sit there fucking analyzing beer. It's antithetical.

It's the same way -- I've sat at tables where somebody's bringing out one fantastic, life-changing wine after another. But, you know, just give me the name, tell me where it's from, and that's OK. I don't need to know what's out of the fucking hill, or who put the grapevines in, or that they were transplanted. I don't need this. I drank it already, dude. I just -- I don't care.

So what's the difference between food snobs vs. beer snobs, in your opinion?

Bourdain: Well, I think snobbery is bad, period.

Are beer snobs more extreme?

Bourdain: I think people's expectations of me, as far as what I'm eating, are already pretty low. They think that I'm a known quantity, that I'm a cheap date, that I like street noodles pretty much more than anything. But I think they somehow expect me to have better taste in beer than whatever generic green bottle I happen to be grabbing. And they see that I'm passionate about food, why am I not passionate about beer? I just ain't. I'm just not.

Also, it's different, because the show is more about going and finding the food, not the beer, right?

Bourdain: Well, beer -- visually speaking, it's why we generally don't do winery scenes or brewery scenes. Because no matter how good it is -- this might be one of only five remaining bottles left on Earth, Napoleon may have put it in the bottle -- but visually, it's red stuff going into a glass. There's nothing to differentiate it from a big box of Gallo Burgundy. It's just not visually interesting. And also, I don't really care. Even with wine, I'm happy, maybe even happier, drinking some local stuff at an agriturismo.

It's an argument I have with Ripert all the time. I'd rather order a Burgundy, not knowing what I'm doing. Let's see. They're so unpredictable. I know nothing about them. It's always a surprise. Spin the wheel. Some of them suck, some of them are going to be good, some will be interesting -- that's interesting to me.

In Appetites, you write, "Home fries almost always suck," and that you're not really into breakfast potatoes in general.

Bourdain: Yeah, personally, I think a lot of this is rooted in the fact that, for most of the low points of my professional career, I was a breakfast or a brunch cook. So it was the default setting when everything else went wrong. So it's the smell of failure. And I knew that the first thing you do in the morning, when you go into your brunch shift or your breakfast shift or any short-order shift, is you put the fucking home fries on. And you make them in huge amounts and you re-heat them. Most of the home fries I have in diners are not good, they're not cooked all the way through, they're not crisp. It's possible to make a good home fry, I'm sure somebody does.

I'm much more OK with hash browns. I like potatoes, I like hash browns. I just don't think structurally they're an ideal potato. I don't think they bring anything to the eggs -- and I like a nice, runny egg -- compared to a big hunk of butter wheat toast. Mingles perfectly with a runny yolk and soaks it up. And you can, you know, drag it across the plate. And how much starch do you need? We're a fat fucking nation. I'm hardly an advocate for healthy living, but it seems to me a big pile of buttered toast is good, bacon is good, sausage is good, eggs is good. Do we really need the potatoes also? I'm not convinced that we do.

It's almost a default breakfast side.

Bourdain: I know what we saw making it as: it fills up a third of the plate. It makes the plate look full. And when the plates came back from the dining room, more often than not no one would touch the potatoes, or they'd pick at one or two, they didn't eat 'em. So it just was, here, you're making these mountains of these things that are good for a while, but they're invariably cold, or burnt.

Or there's, like, that big chunk that hasn't been broken up. Like, the big potato thing that's hidden underneath the lump and you're like, Aw, man, damn these potatoes!

Bourdain: They're sad. You know what David McMillan calls "the scavenger hunt of sadness." You know? It's just one of those things that's like, "Aw, dude." That gives me the sads, that doesn't uplift me or make me happy to be alive.

OK, the food that everyone else seems to like that makes you go, "Eh."

Bourdain: I don't much like scallops. I can eat 'em. I do, I will. But I mean, I don't really like 'em. I don't like black licorice. I live without dessert much of the time -- I mean, because of the jiu-jitsu and because I'm just not really a sweets guy, I'm much more of a cheese guy. Very proud of the dessert chapter in the book, by the way, because it's pretty representative of how I feel about the world.

What's your favorite dessert?

Bourdain: A little something -- well, there's some from my childhood that, of course, I have a grip on. You know, my mom's creme caramel. Obscure old Escoffier era stuff that you never see, I kinda like. Chocolate: a little piece, I don't need a lot. But very, very rarely. I mean, if you'd never served me dessert, I really wouldn't miss it.

Did your family go out for fast food very often when you were a kid?

Bourdain: You know, I am so old that it was considered an exotic treat to go to, like, Burger King or McDonald's. That was not something that I had prior to age, I dunno, maybe 8 or 9. So it was very exciting and not something you did a lot. As a teenager, I mean, you know, I was indifferent to it. I'd eat whatever was in front of me. But that was a part of my upbringing. But I did grow up in a time where the TV dinner was seen as freedom. It freed us from the tyranny of the family meal.

Swanson TV dinners.

Bourdain: You know, so those are roots flavors, too. That Swanson meatloaf with the fucking brownie -- that meant you didn't have to sit at the table. You could eat in front of the TV. That was liberating -- at least we thought of it at the time as this liberating modern, you know, wonder food. I don't have to sit here and answer questions about what we did? I mean, who wants to hang with their parents at the dinner table, really? I mean, they probably should. I mean, now that I'm a dad, of course, I don't want my daughter to eat in front of the TV. I want her to sit at the table with me in an organized meal and I'm like a Jewish mom. I'm like, "Honey, you don't like your food? Eat, eat." I try to express love through food in a tyrannical, overbearing way. And I die a little bit when she says, "Can I just eat in front of the TV?" I'm like, "Aw, fuck." So I've become -- as maybe all of us do -- my parents in some way.

If you had to pick a national meal or food item that every US citizen should know about, which would you pick?

Bourdain: Well, I don't know, what represents us now? I think our number one food -- and most beloved, too -- is like nachos, I think. I think it's the most widely eaten and loved. Nachos, burgers, or pizza would be the obvious answer. I mean, the burger seems to be our most successful export and we're still better at it than everybody. I don't know -- maybe you go pastrami on rye, a nice pastrami. It would be immigrant food, for sure, whatever my choice. What I would like to see is -- maybe something that represents the melting pot -- is the army stew that's such a mash-up of the American/Korean experience. That would be nice. And it might well happen.

Because who's driving the bus right now? I believe it's, to a great extent, Korean-Americans -- and Asian-Americans in a larger way. But I think that people like Roy Choi who ate one way at home and grew up with tacos and burgers, I think that's the sensibility that is going to be driving the bus for the next decades.

Completely agree. How do you think eating with Clinton or Trump would compare to your Vietnam meal with President Obama?

Bourdain: I don't know. I mean, I don't know. I've met Secretary Clinton. Backstage at Jimmy Fallon maybe. She asked me where I was going and I said, "To the Republic of Georgia." And she said, "Oh, my God, the drinking there and the cheese." We talked about food. She seemed interested. Obama's a foodie and he's got good taste in restaurants. And he's very sentimental about the street food of Southeast Asia. Very. You know, he spent a lot of time in Indonesia as a young man. And the meal I had with him -- he talked very emotionally and wistfully about the smell of Indonesian street food. I could see just how much he was digging bun cha. I've never seen a man so happy to drink a beer from the bottle, you know? So I think he'd be the most fun.

And Trump?

Bourdain: Trump would be interesting, because watching him struggle with chopsticks would be pretty fucking hilarious. And he is allegedly a germophobe and he eats his steak well done. So you know, seeing him at a state dinner -- like, a Chinese banquet, and trying to deal with the hospitality there -- would be pretty fucking hilarious. How does he even grab chopsticks with those little fingers?

Do you know anything about Pokémon Go?

Bourdain: I see the zombies in the street now. Fine, you know? At least they're not shooting heroin. [LAUGH]

Do you have a favorite Pokémon?

Bourdain: No. I mean, I am sure I will have to learn for my daughter at some point. I don't think she's allowed online without permission, but it's only a matter of time. We have to download stuff for her under approval, but no, it's inevitable. Clearly, it's coming and I will have to be aware of this. There are more Pokémon Go users than Twitter right now, I'm told. Which is extraordinary. And you know, but look, will it be like Angry Birds? You know, who's doing that anymore?

Right. No one even saw the movie. Maybe because the movie came out so much later than it should have.

Bourdain: Right. It's some great, great thinking out there. The kids are loving it -- what is this Angry Birds thing I'm hearing about? Oh, that's great. I'm gonna love it. You gotta love it. Everybody's doing it. All the kids today are loving it. You know?

Let's talk more about movies.

Bourdain: Oh, good. I love talking about movies.

In terms of depictions of chefs -- and I know you are on the record about this -- there aren't any movies or TV shows that have done it really successfully.

Bourdain: Right, because they get it wrong. Always. There have been exceptions. Look, the plot of Chef, the Jon Favreau film, was a fairy tale. It was a fable, OK? It was completely divorced from reality. But all the details -- the important things to me, the knife work, the choice of -- what did he make at home? The on-camera food preparation, the little touches, like, the discussion about corn starch, it was pretty good.

Right.

Bourdain: I think that he tried really, really hard to get it right and it showed. And I think it was -- I really enjoyed the movie and at no point during the film did was I going, "Oh, this, fuck it." [Laughs.] No, I -- you know, whereas -- I thought -- Ratatouille probably came as close to being perfect as any film ever in portraying the industry. Again, little things. The burn scars on the woman chef's arm. It was pretty, pretty good.

Look, as you might have imagined, I've had a number of meetings, whether I'd be interested in developing a project. And you know, I talk to the principals and usually, there's a star attached who wants or expects certain things. You know? [The pitch is about] a chef and a general manager, and they were in love in the same restaurant. And I'm like, "You know, that's a very short-term situation. That's not gonna work out, OK?" And he's a bad boy, you know? He's gets all fucked up, but now he's back and he's getting back in touch with his passion. But that was Burnt and it was fucking unwatchable. It was agony. I mean, I literally couldn't. I couldn't.

I think people sense when it's not real. The first thing that I always hear is, "People don't talk like that." They don't talk like that. And it's just all wrong. Al Pacino, Mr. Method Actor, one of the most egregiously awful portrayals of a short order cook in the history of the world in Frankie and Johnny, it's like, dude, what the fuck is wearing the chef's hat or whatever he's wearing, the bandanna. Spend a little time in front of a fucking griddle, at least. All wrong. Mostly Martha was kinda good, I think Mostly Martha got the obsession and the dysfunction and the inability to communicate through another means of food. I think they really nailed that. Whereas, No Reservations, the American version, of course, completely shat the bed and, you know, destroyed an otherwise -- I thought -- great movie. I thought Mostly Martha was very good. I thought Eat Drink Man Woman is probably the best. I mean, that's the benchmark. It gets the heart of the cook. And again, their struggle to communicate through any other means than food.

But nobody has done it right. Nobody has explained in words and in character what drove people to enter the business in the first place, what it is about the business that keeps people in, what's it like going through that system. You know, in a lot of ways, I think Goodfellas would be a good template for the perfect chef story, you know? You know, you're entering a secret society with a moral compass very different than the outside world, but it is a propelling one. With its satisfactions and its perils and its own style and language. And I think you need to pull people in, in the same way that they maybe want to spend time with Joe Pesci, you know? I think there's a story to be made. But I think it needs to be more like Jiro. It's a doc. But it was thrilling because it gave you all of the things that are essential to a story about people who make food. It had food and a character who was fascinating. And who inspired you and broke your heart at the same time.

Random question: Did you ever watch Three's Company?

Bourdain:Three's Company, with John Ritter?

Yeah. He was a chef and opened his own restaurant.

Bourdain: Oh, yeah. But I mean, the minute the chef puts the hat on, they are dead to me. Because the chef is the guy without the hat, you know? So whether it's a floppy hat of a coffee filter, it's just like -- unless you're working the buffet at the Hilton, it's already wrong, you know? Somebody on Friends is supposedly a chef, too.

Monica!

Bourdain: I mean, come on, it's not even worth the words. It was like that terrible film with Adam Sandler -- what was it called? Where they had, like, great chefs literally consulting on it?

Spanglish.

Bourdain: Yeah. It was by the guy who did Broadcast News. James L. Brooks did it. He was, you know, a fucking genius as far as I'm concerned. But this movie. Here's a chef and most of the time, he's nowhere near the restaurant. It's like, I don't know what kind of restaurant you're running, bro, but...

Would you ever want to write a movie? I know you worked on Treme.

Bourdain: Some of the happiest work I have ever done -- the most satisfying and fun and, frankly, easy work I have ever done -- is writing for Treme. I loved being part of the writing team. I loved imagining a room and creating dialogue. That was a very happy experience for me. What I'm never going to do, ever, is I'm never going to write a pitch or a screenplay and then go pitching or shopping it. No, if you want me to write dialogue for you, you put me up in the Chateau for a couple of weeks or a couple of months, I'll be your pony, sure. But I'm not out there trying to sell.

I hate plot, anyway. That's not my thing. I see plot as an imposition. It doesn't interest me. I'm all about atmospherics and dialogue makes me happy. So one of the joys of working on Treme was that you work with a whole bunch of other people who would map out an entire season and then there would be bites for me to fill and get us from here to there. How are we going to do that? What do you think would happen? What do you think this character would do? How would they behave? Who would they do it with and what would they say? Well, that's easy. And fun.

What's the best restaurant or bar industry movie ever -- Road House?

Bourdain: Oh, yeah. It is, I watch it every year. Every year I have a Road House party, usually.

Wait -- you do?

Bourdain: Yeah, out at wherever place I am renting in the summer. And I will invite people over. We will drink a lot and we will watch Road House. It is just awesome.

That's amazing. Like the movie.

Bourdain: You can just analyze it forever. It's just peeling back the layers of an onion, you know. The subtext is just so great. When you try to beat up the same guy three times, don't you go get a gun, you know what I'm saying? What the fuck, dude? And what criminal enterprise is [the guy who played] Jackie Treehorn in anyway? I mean, it's all about a fucking Road House -- really? And a used car dealership? He's not even selling meth.

And the bar doesn't seem to be particularly well-run, either.

Bourdain: It's interesting -- it was better before [Dalton arrived]. Like, later on, they are playing Kajagoogoo or something in there. All these people with mullets and horrible puking frat boys and date-rapists. It's like, this is not good. These are the people that you want to keep out of your establishment. Bring back the cowboys. But I love it. And they are remaking it with Ronda Rousey, right?

Yeah.

Bourdain: Oh, I would like to be on that. [Laughs.] I would love to write dialogue for that.

Like if the producers added in kitchen scenes?

Bourdain: Yeah, in a hot second. Are you kidding me? I would do that for anybody. You know, rewrite. Somebody just did a really shitty job on this kitchen movie that we just did. Can you fix the dialogue? Yes, yes, I can. I promise you I can do that. Or you know, write some kitchen scenes for John Wick 4. Fuck, yeah. There's a John Wick 2 coming soon, which I am super-excited about. As a jiu-jitsu guy, it's like crack for me. I think it was the greatest, really, one of the greatest films of last year. It creates its own world. There's no plot, it's perfect. They killed my dog, so I'm going to go kill everybody. That's a plot. It's my kind of plot.

It's like the better version of Taken.

Bourdain:Taken Again? Jesus Christ, you know, it's like a professional kidnap victim, that kid. I can't watch women-in-peril or kids-in-peril movies. I can't do it. I'm physically incapable. I won't watch it. They are just too manipulative, and it works, you know? The wife captured and tied to a chair or the kid. It's just -- aw, dude. And there are scenes, also, like the sleeping child scene, you know? Where he's a bad man, he's killed a lot of people, but there's that scene where he looks longingly at his sleeping son. It's like, come on, man, you know? We get it. We know you've got a soft side. But yeah, I really enjoy that kind of writing. I don't have time to do more, but I would happily do more.

Hired! Thanks for doing this interview. Good times.

Bourdain: Well, thank you. Again, I'm sorry I was so late.

Anthony Bourdain's Appetites: A Cookbook is out now.

Sign up here for our daily Thrillist email, and get your fix of the best in food/drink/fun.