Why Are So Many Great Atlanta Restaurants Closing?

If you’re a fan of eating food in Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward, the name 4th & Swift -- owned by chef Jay Swift, who earned recognition by reinvigorating the menu and vibe at one of ATL's most beloved spots, South City Kitchen -- should ring a bell. The restaurant had an eight-year run and featured some of the most inventive dishes in Atlanta (the menu is still live on their website if you feel like torturing yourself and imagining what the Bramlett Farms trout a la plancha with chanterelles, blackberry, pistachio, basil, and charred broccolini tasted like).

In terms of restaurants reinvigorating the O4W, some would claim 4th & Swift planted the first flagpole. Everything had a local -- or regional -- flair, thanks in part to its proximity to food purveyors down the interstate. And Swift earned heaps of praise during the restaurant’s reign, including Restaurateur of the Year at the 2012 Georgia Restaurant Association’s Grace Awards ceremony. When he isn't winning prestigious awards, he promotes state farmers markets as a member of the non-profit Georgia Organics. He’s been invited to cook at the James Beard House. And he's an avid supporter of The Giving Kitchen, the organization that provides emergency financial assistance to restaurant workers facing hardships.

Staplehouse, the Atlanta restaurant everybody’s currently saying is the best new place to eat in America, donates all its post-operational revenue to The Giving Kitchen. Swift is one of Staplehouse’s founding members. Therefore it was a tough pill to swallow when we found out he rolled up his knife bag and headed to Peachtree Corners to open a new restaurant called Noble Fin -- an American steak and seafood joint. It's hard to be upset with Swift for going full Braves on us and taking his talents to Gwinnett County, though. That's where the money is... and presumably, way more pudgy people. But it does say something about Atlanta proper. We ultimately didn’t appreciate the fancy local fish Swift plated, so he left.

There are also places like The Spence, which shuttered this past summer. But there was a time when it was Richard Blais’ super-supper sanctuary where everything looked straight out of a celebrity chef TV show. Hanging pots, pans, and knives, serving dishes that would smoke your meat as it made its way to your table, and an open kitchen that allowed everyone to see what was happening on the line. Perhaps the problem was the location. Being on a strip in the middle of Georgia Tech, where kids want burritos and fast teriyaki, certainly isn't conducive to upscale dining. And let's not forget Blais made his bones via burgers -- FLIP was one of the pioneers of ATL’s massive burger wave a few years ago, but ultimately had problems bringing $6 “haute” dogs to Virginia-Highland. And, let's face it, if anybody has the money for premium frankfurters, it’s VaHi.

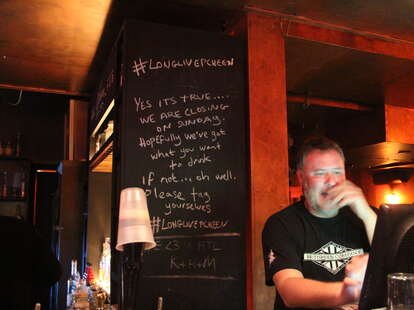

Going back to the O4W, and one of the trendier places that plenty of folk still miss dearly, is P’cheen, which was run by a group of partners that included Mike LaSage of Bone Lick BBQ, Alex Friedman (currently at bartaco), and Keiran Neely, who runs The Music Room -- adjacent to the Edgewood location of Bone Lick. P’cheen closed in early 2014, and was replaced by Last Word, which had developed quite a reputation for cocktails and food, but had sharp changes in direction and ultimately shut down last month.

Neely doesn’t mind being brutally honest when he talks about the closure of P’cheen and how it signified broader changes coming to the O4W. “The beginning of the end was when all the new restaurants started popping up down Highland Ave and around the corner -- the likes of Barcelona Wine Bar, an independently owned chain with very deep pockets -- and the subsequent onslaught of other brand-new, sparkly, see-and-be-seen places, which were way more attractive to the new breed of single hipster wannabes, who had started to make their homes and spend their social time in the now ultra-cool O4W. By 2012, P'cheen was showing wear and tear; it was definitely no longer the only place in the neighborhood. The dynamics of the O4W residents had definitely changed.”

"The beginning of the end was when all the new restaurants started popping up down Highland Ave."

However, that doesn’t mean he was happy to see the restaurant that replaced P’cheen go away; “It's always sad to see a mom-and-pop, independently owned restaurant close. Having been through the pain of closure, I know what it's like. I guess the real questions are: do you think there are similarities between why P'cheen closed and why Last Word closed? Were P'cheen, and subsequently Last Word, just too far off the beaten path with lack of parking? Is Atlanta too fickle? Are we more interested in the see-and-be-seen -- the bling -- than the food/drink? Yeah, some of us are.”

But Neely's last statement begs a question: why are some of the bling-ier spots closing as well? When Angus Brown and Nhan Le opened a more mainstream (but incontrovertibly fancy) seafood spot, Lusca, in South Buckhead in 2014, people assumed that the duo who’d sucker-punched ATL with Octopus Bar (an instant favorite late-night East Atlanta Village restaurant) would be a shoo-in for success. It even was a James Beard Award Best New Restaurant semifinalist in 2015. But apparently drawing people in from outside the Brookwood Hills area was more difficult than they’d anticipated, and they never flipped enough tables to turn a profit -- even though they counted big names such as Ford Fry as fans. “[Lusca] truly showed Angus and Nhan’s passion,” Fry says. “Angus on the stove and Nhan on the raw side.” Another fan was Matt Coggin, chef/partner at DBA Barbecue, who called 4th & Swift’s closing “a sign of the times.” That said, Brown and Le aren’t letting themselves get too beat-up about the loss of Lusca though; they’ve now opened 8arm, another sea-monster-named coffee shop/restaurant open from morning to late-night near the BeltLine around Virginia-Highland. It’s safe to assume they’re hoping the area’s notable foot and car traffic will keep their new venture afloat.

Speaking from the business side, Coggin offers several reasons why the outlook is full of black smoke. “Too many restaurants have opened in the last two years,” he says. “PCM, Krog Street Market, and Inman Quarter have all opened within one mile of each other. It's just too much. Areas that were once considered premium retail/restaurant are lacking in foot traffic, but rent is still reflective of a premium location. There are not enough skilled hospitality workers to fill all of these restaurants. This has increased the cost for quality labor. If fast-food employees receive $15/hr as a norm, full-service restaurants will be doomed. Affordable Health Care is anything but affordable for a small business owner. My cost to insure my key employees has tripled. I actually just changed our business structure to avoid having 50 full-time employees.”

For his part, Ford Fry has had success opening places like JCT Kitchen, The Optimist, King + Duke, St. Cecilia, Superica, Bar Margot, and Marcel, so if there's anyone who knows how to beat the odds, it’s him. “I think that from 2008-2012, Atlanta (as everywhere else in the country) slowed way down on opening restaurants. 2012 was the surge, and Atlanta had a bunch of great restaurants open, scattered all throughout the neighborhoods, as opposed to the major streets like previous generations of restaurant growth. So compared to the growth, I feel that the closings have more to do with individual reasons. The one that surprised me was 4th & Swift. I had thought that PCM would have driven more to the area, but I’m thinking it added to the popularity of more casual dining.”

"I think new restaurants need to be truly authentic. I think it's important to be what the neighborhood needs."

When asked what it’ll take for new restaurants to survive and not fall victim to a similar fate as 4th & Swift, Fry continues, “I think new restaurants need to be truly authentic, super-humble, and genuinely excited to provide fantastic dining experiences. Even before all of that, I think it is important to be what the neighborhood needs to complement what it already has. We need to remain fresh and diverse.”

These rapid changes are also affecting suburban cities like Brookhaven, where Pub 71 closed this summer after 10 years of providing pints and plates to locals. Another tragic loss was The Pecan, a popular upscale Southern restaurant run by chef Tony Morrow, who opened a barbecue restaurant just a few blocks down on Main St a couple years ago. While prices at The Pecan were infamously not cheap, the food and service were always well-rated, and it was one of few places near the airport that would regularly attract guests who lived north of Downtown.

And it doesn't end there. There was Corner Tavern, which closed its West Midtown location on Huff Rd last year, prior to the closure of Bone Lick BBQ, which opened in the same complex down the street and closed its doors over summer. The area is on a perpendicular cut street between Marietta Blvd and Howell Mill, meaning it gets limited traffic and may not be ideal for the type of urban-chic customers these restaurants have sought. So although the signs on the storefronts have constantly been in flux, there's always been a consistent: location, location, location.

"There have to be more closings. Ten to 20 years ago there were maybe two places I went to get BBQ. Currently I can think of 20."

Mike Rabb, who, with his wife Melanie, owned West Midtown Corner Tavern (as well as the original CT in East Point), agrees with Neely’s thoughts on what causes the closures, saying that overbuilding in town, high rents, and less parking have made it harder for customers to get to their restaurants and for them to turn a profit. Melanie sees things pessimistically when predicting the future: “There have to be more closings. Ten to 20 years ago there were maybe two places I went to get BBQ. Currently I can think of 20 places I like and want to check out. Vegas odds would be that an increased turnover is a given.” She also things that management plays a major part in making your restaurant economy-proof.

“The way we used to run restaurants back in the day just won't work. For a restaurant to survive, it's got to be well managed -- not just from the staffing end but from a numbers perspective. Profit margins have to stay tight; there isn't as much room for loss of revenue. You have to be smarter and more controlled with your inventory.”

Ultimately, it seems there's a perfect storm of uncontrollable factors that are killing some of our greatest kitchens: gentrification, increasing rents, higher food costs, and locations that aren't as fertile as aspiring businesses had hoped. Maybe, as Melanie Rabb says, there’s too little between the margins to play around when it’s time to turn a profit. Maybe, ironically, what Atlanta’s restaurant industry needs is just a little more belt-tightening. Then again, maybe we’re franchising our supper sensibilities out to fast-casual smartphone-compatible food, and we’re all in too much of a FOMO-induced state -- insatiably foaming at the mouth for whatever future flavors are in the next bite. Whatever's happening, hopefully it won’t result in ATL becoming a real-life version of Demolition Man, in which we tear down all of our greatest restaurants and turn everything into a Taco Bell. Because sure, Atlanta is popular and more people are moving here, so there's no doubt more condos are coming. But let’s not lose the thing that makes everybody want to come, live, and eat here with us: our exceptionally good taste.

Sign up here for our daily Atlanta email and be the first to get all the food/drink/fun the ATL has to offer.