He Wupped Batman's Ass: The Complex Simplicity of Chicago Legend Wesley Willis

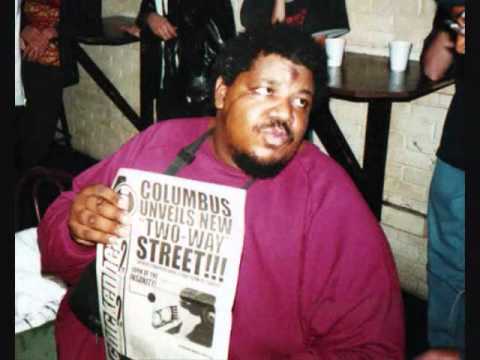

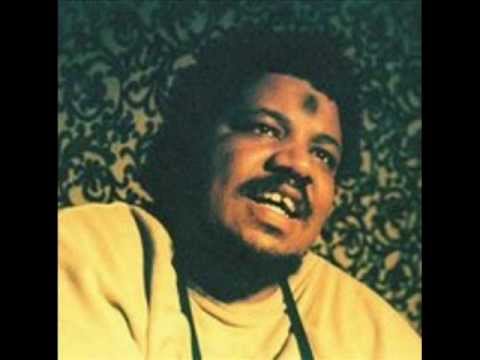

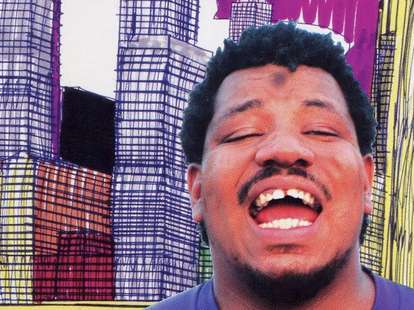

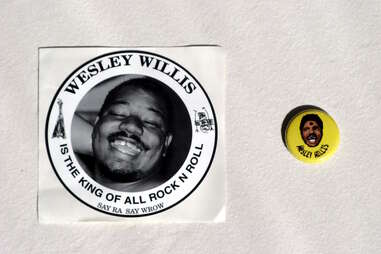

“Are you ready to fucking rock?!” The hoary, KISS-worthy bit of clichéd crowd work is delivered with no traceable irony. It comes courtesy of a man who otherwise appears diametrically opposed to any kind of rock-star convention: a 300lb, sweat-suited, diagnosed schizophrenic from Chicago named Wesley Willis. His forehead is permanently bruised from greeting fans with loving head-butts. He’s plopped at his Technics keyboard, ready to hunt-and-peck pre-set melodies so rudimentary they make minimal-wave synth sound like baroque opera.

The room roars back, giving Shea Stadium in 1965 a run for its money. “Yeeeah!” A hint of skepticism is detectable in the crowd, however. How could there not be, at such an introduction, so impossibly full of naïve joy? The question of exploitation is necessary, but right now the artist is either oblivious or unconcerned. He’s already launching into “Chuck Hazelwood,” like so many other Willis tracks an homage to a personal fixation, belted out with maximum enthusiasm and zero vocal range.

The apeshit crowd shouts back the hook, full throat, with each (frequent) repetition. The frenzy peaks with a Carolina-tailored version of the patented Willis coda: “Rock over London, Rock on Chicago,” followed by his trademark drop of random corporate ad sloganeering. “BMW / It’s the ultimate driving machine!”

That particular show took place 15 years ago, at Kings music club in Raleigh, North Carolina, near the end of Willis’ supremely unlikely career as visual-art and rock star. Today, it plays like a time capsule from the long-ago era that cast perceived lack of self-awareness as the ultimate authenticity. Right up until Willis’ death from leukemia in 2003, his astonishingly simple music operated in that complex bramble, perpetually raising questions about self-consciousness, “realness,” and spectatorship that -- despite shifts in critical approach -- still linger today.

“Willis didn’t boldly break the rules, because he didn’t know there were rules.”

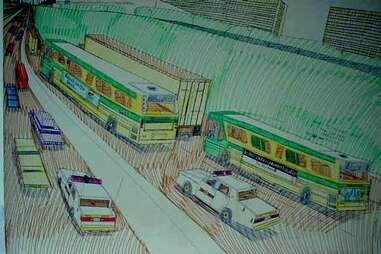

To appreciate that relationship, it’s important to first understand some biography. Willis’ local ascendency actually began before his music career, with ink-pen drawings he composed and sold on Chicago streets in the late ‘80s. Even today, it’s not uncommon to find displays while navigating the city in museum exhibitions or neighborhood bars like Quenchers Saloon. He procured materials at Genesis Art Supply, which is also where he hooked up with future bandmate Dale Meiners and future roommate Carla Winterbottom, both key to his musical turn.

He matter-of-factly announced, “I’m gonna be a rock star” and soon began composing lyrics. In the time it takes most acts to agree on a drum sound, Willis would amass a survivalist-sized stockpile of tunes, spread across dozens of albums.

Famous fan-turned-friend Jello Biafra (Dead Kennedys, Guantanamo School of Medicine) released the first of an eventual three Greatest Hits collections in 1995, and the spotlight was firmly squared. As pointed out by Eric Strom, organizer of last week’s Wesley Willis Tribute Night at Beauty Bar, cuts like “Alanis Morissette” and “Cut the Mullet” peaked onto broader radars, with the former hitting Buzz Bin-era MTV and the latter finding subsequent ubiquity in the early days of file-sharing.

As idiosyncratic and improbable as the hits were, Willis’ music and semi-stardom fit a tradition. In Songs in the Key of Z: The Curious Universe of Outsider Music, author Irwin Chusid positions Willis alongside primitive favorites The Shaggs, Daniel Johnston, Jandek, and Syd Barrett, among others. The unifying impulse is a belief in the inverse proportion between self-awareness and genuineness. “They don’t boldly break the rules, because they don’t know there are rules.”

“[I Wupped Batman’s Ass] was audacious, weird, and funny. It made sense to a 16-year old who discovered irony last week. Then you get to ‘Chronic Schizophrenia,’ audacious became vulnerable, weird got lonely, and it wasn’t funny anymore.”

The Peter Pan romanticism of innocence often leads to choppy waters, and Willis’ mental-health condition only further necessitated a kind of self-audit on the part of listeners. Vincent Chung, a former Punk Planet contributor who hesitatingly attended the 2001 show at Kings recalls the struggle, starting as a teenager interpreting “I Wupped Batman’s Ass.” “It was audacious, weird, and funny. It made sense to a 16-year old who discovered irony last week,” says Chung. “Then you get to ‘Chronic Schizophrenia,’ audacious became vulnerable, weird got lonely, and it wasn’t funny anymore.”

He clearly puts forth the central conflict: “Am I laughing with a goofy, outrageous showman -- or at a tortured, diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic? A creative talent? Or a minstrel show?”

Do not presume a lack of agency that Willis, by most accounts, indeed possessed. Winterbottom, a Chicago-based artist who roomed with Willis for roughly seven years during the ‘90s, describes a man who couldn’t cook or tie his shoelaces, but was also an extraordinarily self-driven artist with a shrewd sense of promotion.

“He was savvy enough to realize what sold. If he wrote you a love song, you were gonna buy a few copies,” says Winterbottom. “And the same with the band tributes. He was a very smart marketer. In a sense, Wesley exploited his audience as much as anyone could’ve exploited him.”

Winterbottom’s take on the music itself is instructive, too, finding more craft and intentionality than might appear at first blush. “He took it very seriously. He’d pick around on the keyboard. He was very specific about finding the right key and tempo. He’d work it out musically. Wesley crafted his music according to his own style -- it’s kind of charming and childlike but also introspective and uplifting.”

A similar picture emerges in regards to Willis’ visual art. Invoking the names of Chicago-based self-taught notables Joseph Yoakum and Lee Godie is a logical progression when discussing Willis with Leonard Cicero, exhibitions coordinator at local outsider-art museum Intuit. “I do place Wesley in the same category, based on lack of formal training, vast output, and obsession with a specific style and limited subject matter.”

“... he saw beyond the physical as represented in his drawings and understood the intricacies of fast-food-fueled, fast-paced corruptible urban living.”

As with his music, Willis’ instantly identifiable visual technique often played like a formal vibrant exercise in civic advocacy. “What stands out to me is Wesley's interpretation of the city of Chicago and his ability to accurately render perspective and scenery while creating a unique mood,” says Cicero. “His coloring and line work... remind me personally of late ‘80s/early ‘90s Chicago. His blues, pinks, yellows, and reds remind me of graffiti, b-boys, and wearing baggy designer jeans that were three times too big.”

Cicero finds that purposeful minimalism in the songs, too, notably “the brilliance of his lyrics and ability to critique pop culture with the turn of a couple phrases and preprogrammed rhythms.” He also locates the social-critical component, which still too often goes unnoticed. “[Willis] let you know that he saw beyond the physical as represented in his drawings and understood the intricacies of fast-food-fueled, fast-paced corruptible urban living.”

Even if one doesn’t share an affinity for Willis’ music (and somereally don’t), his sheer resolve against truly bleak obstacles points to further self-empowerment. Chusid, for example, finds Willis a difficult listen that fails to hold his attention, but still speaks admiringly of his “hallucinatory perspective,” creative process, and “perseverance and prodigious output.” As Strom puts it, “he’s a great example of how Chicagoans support outsize personalities and people who get shit done, warts, weirdness and all.”

The implications extend beyond art, as well. His continued significance in particular to fans who face similar struggles bears that out. “I get emails and calls from kids around the world, sometimes with mental illness,” says Winterbottom, “and it means something for them to know that he did okay for a while and lived his dream.”

Anyone who attended the recent Wesley Willis Tribute Night at Beauty Bar with such heady critical questions in mind -- not to mention images of remarkably raucous crowds from the old days -- encountered something much more subdued. Several dozen fans mingled about, taking in Willis-inspired art, watching a screening of The Daddy of Rock 'n' Roll, and bopping along to the Jollys, a local garage-pop outfit that could have easily provided source material for a Willis ode were he alive today.

There was little in the way of moral anxiety or fraught spectatorship. Thirteen years of distance helps that, so too does our collectively more nuanced critical capacity -- an embrace of craft and deliberation that complicates narratives of self-taught artists as unstudied, unaware vessels. Looking back on Willis’ prolific full-steam-ahead career, his brilliant appropriation of brand promotion, and his autonomous artistic cogency, you start to feel like he probably reached that breakthrough some quarter century ahead of schedule. Rock on, Wes.

Sign up here for our daily Chicago email and be the first to get all the food/drink/fun in town.

Stephen Gossett is a Thrillist contributor who just now cut the mullet. Follow him on a harmony joy ride: @gossettrag.