'The Godfather' and Earthquakes Inspired 'Pachinko'

Soo Hugh, who created the Apple TV+ adaptation of Min Jin Lee’s bestselling novel, talks about the movies, historical events, and books that influenced the show.

When considering the many influences that went into making the new Apple TV+ drama Pachinko, one must start at the source: Min Jin Lee’s bestselling family epic. Like the book, Pachinko tells the story of a family legacy, starting with Sunja, a young girl born to modest parents who run a boardinghouse in Japanese-occupied Korea in the early 1900s. Over the course of eight episodes, the audience sees a teenage Sunja (Minha Kim) become the mistress of a high-class Korean fishmonger, a wife to a sickly pastor, and a mother raising two Korean sons as an immigrant in Japan. At the same time, Pachinko chronicles an older Sunja, now a grandmother (played by Youn Yuh-jung) who must face her past after her grandson, Solomon (Jin Ha), returns home.

Though the bones of the story remain the same, adapting a 500-page novel into an eight-episode series necessitated many changes. Some of these changes came from the series' development. Creator and showrunner Soo Hugh (Under the Dome, The Terror) originally envisioned Pachinko as four seasons; as such, the first season only covers about one-fourth of the book. But other changes were inspired by Hugh’s own historical research and her desire to tell a story that honored the experience of Korean immigrants who experienced discrimination in Japan in the 1900s.

As Season 1 of Pachinko aired, Hugh spoke to Thrillist about what inspired the many differences between the book and the show, and why it was so important for her to have that killer opening-credits sequence.

The Godfather

One major difference between the book and the TV show is how it’s told. Lee’s Pachinko unfolds linearly, but Hugh’s interpretation frames the story first through Solomon, Sunja’s Japan-born grandson, who returns to Japan for work. The show jumps back and forth between two main timelines: Sunja’s youth and her grandson’s return in the 1980s. Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather trilogy was a key influence for Hugh, who was specifically inspired by The Godfather Part II to see how Coppola integrated the Corleone family past with the present.

When I pitched this to Apple and the buyers, [Godfather II] was one of the references that I said. Godfather II in lore has now become a crime story, but when you actually watch the movies, especially the first two movies, it's a family story. And crime is definitely an element of that family, but at the heart it is a story about, “What does a family become? What are the choices a family makes?” And so that was definitely a big inspiration for us in the writer's room, especially the second film.

I love how in the second movie, even though Marlon Brando is not in it, you're still taking on the myth of that father figure with a De Niro character. … Nowadays I feel like Francis Ford Coppola would've made the Godfathers a TV show.

When I was much younger, I had seen The Godfather Part I on TV. They actually put [Part II and Part III] together. They televised a version where they put the two films together and had to re-edit it. And I thought it was a lesson in what not to do with time. Because by making things too smooth in those time jumps in that TV version, you realize time loses its energy. But sometimes some of that ambiguity and some of that question of how these timelines relate to one another gives it that spark.

Historical texts and the labor movement of 1930s Korea and Japan

For Hugh, writing the show wasn’t just about getting the family epic onto the screen—it was about expanding the story. That meant research—and lots of it—in the form of historical texts and 20 history consultants, including those specializing in “Japanese history, Korean history, and colonization.” As she learned more about the history of Koreans in Japan, Hugh decided to tweak the story of Isak, Sunja’s pastor husband. In the book, Isak is arrested after another pastor refuses to pledge allegiance to the emperor, but in the show, Isak is arrested for rebellious acts against the Japanese government.

As I was digging more and more into the history of this time period and working with various historians and consultants, I just went down the rabbit hole of 1930s politics in Japan, especially the politics of the labor movement and the plight of so many of these marginalized communities in Japan at the time. I desperately wanted to see more examples of people who tried to fight back or tried to create a better life for their children, who said, “These are terrible circumstances, but I'm going to keep fighting and I'm going to keep yearning for a better day.” And it was such a fascinating time in history that I really wanted to bring that politics into the show.

The Great Kantō earthquake of 1923

Hugh’s research also led her to the Kantō earthquake, which hit the Tokyo-Yokahama area on September 1, 1923. The quake’s impact was massive, with a death toll believed to total at least 140,000. In the aftermath, Korean immigrants became scapegoats, with rumors that they were adding to the destruction. This led to massacres, and the Smithsonian reports that an estimated 6,000 Koreans were killed as a result. That inspired another major change from the book: giving Sunja’s upper-class lover, Hansu (Lee Min-Ho), a backstory in Episode 7. In the book, Hansu is much more of a villain who seduces a much-younger Sunja and leaves her pregnant and unmarried, but Hugh wanted a different approach for the show.

[In] the research that I was doing about Korean history in Japan, I came across the Kantō earthquake. I had never heard of the Kantō earthquake; I had never known about just what a devastation it was upon Japan. And then to hear about the violence that came upon the Koreans, I was really shocked by it, but more important that I realized [it answered so many of] my questions about Hansu: “Who is he? Where did he come from? How does someone like him become that way?” All of a sudden, things just started to realign themselves in this really elegant way. And I thought about the Kantō earthquake, and all of a sudden in framing him with that background and that history, he became a fully fleshed, three-dimensional character to me.

I'm not interested in doing heroes and villains. I just don't believe it represents life at all. And I don't think it represents the ambitions or the heart of a show like this, which just says, "We're going to tell the story about a kaleidoscope of humanity in our own way." And that means people have to have backgrounds. People have to have had a life lived. And whether or not you like a character, you have to accept them as human. And so with Hansu, I find [him] to be an extremely complicated figure, [but] when I think about the Kantō earthquake, it just makes that character feel more lived-in.

Hidden Treasures: Lives of First-Generation Korean Women in Japan by Jackie Kim

Hugh says that the writers all read countless historical texts “to make sure that the story rang as true as possible,” but she especially took inspiration from Hidden Treasures, a work by Jackie Kim that inspired the ending of the season, which includes real interviews with women who immigrated from Korea to Japan at the same time as Sunja.

I was so inspired after reading her book because she has really dedicated her life to capturing the final, the oral testimonies of these first-generation. There's not that many of them left with us. … So it just feels urgent that we try to capture as many of their stories as possible. And so her book was very seminal for us.

Originally I thought it would be nice to end the whole entire series—if it was meant to be four seasons—with finally meeting these women, and reminding audiences that these characters that you've lived through for all these years, their stories come from actual events that happened, even though we're not a true story. … And as our first season went on as we were writing and during the prep, I just had this feeling of like, "You never know when a series is going to come back. You don't know how long it's going to take. And also, I don't know how many more years some of these women have.”

I just felt an incredible urgency about those interviews. … And at the end of the day, I told myself, “I love these women. I love their stories. I love the bravery that it took for them to tell their stories at their age.” And so I wanted the audience to feel that as well.

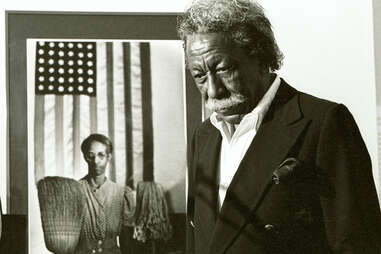

Gordon Parks' photography

Pachinko rejects the idea that everything in the past has to be sepia-toned or washed-out to signal time gone by. Instead, the show is full of lush, pale colors, giving a vibrant energy to Sunja’s youth in Korea and Japan. But for Hugh, the inspiration for the Pachinko color palette actually came from iconic black-and-white photographer Gordon Parks.

What I love about Gordon Parks’ color and his framing is his blacks. I feel like so much of TV and film nowadays, I miss inky black. But the reason why I think that color palette works really, really well and doesn't feel just pure nostalgic is because we have these harsh, hard blacks in the frame as well to balance the creaminess. One of the words in the color suite we always said was "creamy, creamy, creamy.” Where's the creaminess in this image? But whenever we have that creaminess, it had to be balanced by black.

Opening-credits sequences

Pachinko features an infectious opening-credits sequence that invites the main cast to dance in the pachinko parlor run by Mozasu (Soji Arai), Sunja’s son and Solomon’s father. The sequence is the only time the actors from the past and present intersect, and was inspired mainly by Hugh’s own love of opening credits.

I wrote the title sequence into the script. I love the title sequence. I just come from the background where I watch title sequences religiously and I will Google title sequences and just watch title sequences. I think they're very much an art form, and a good title sequence tonally sets the stage for that cinematic experience.

The mandate for all the title sequences always is we do something that [the audience is] never going to skip over. They have to watch it week-to-week.

The Joy Luck Club

It’s impossible to look at the history of Asian stories being told in Hollywood without looking at The Joy Luck Club, Wayne Wang’s 1993 adaptation of the book by Amy Tan, and famously the only Hollywood movie with an all-Asian cast until Crazy Rich Asians was released in 2018. Though The Joy Luck Club didn’t directly influence Pachinko, Hugh made sure to give the movie credit for breaking barriers.

We’ve always said, “Let’s do the show the way we need to do the show.” I think every story needs to be told in its own unique way, but without a doubt, Pachinko would not be here without The Joy Luck Club. I owe such a huge debt to The Joy Luck Club, and not just Joy Luck Club, but to Minari, to Squid Game. And even non-Asian movies that broke ground—without them, we would not be here, period.