Wisconsin’s Shipwreck Coast Is Filled with Stories Past

Plus some present-day quicksand, and one Christmas Tree Ship.

Unless it’s, say, the Titanic, shipwrecks don’t often make it into commonplace lore. But one 109-year-old wreck deep in Lake Michigan’s chilly waters has wedged itself into the fabric of the Great Lakes, inspiring plays, stories, art, and even songs about its demise. And understandably so.

The weathered Rouse Simmons schooner—widely known as the Christmas Tree Ship— went down just north of Rawley Point, Wisconsin, on November 22, 1912. Helmed by Captain Herman Schuenemann (nickname: “Captain Santa”), it was carrying precious holiday cargo, taking trees from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula to sell in Chicago. There were approximately 16 men on board, crew members plus a few lumberjacks hitching a ride. “He was a benevolent man,” says Tamara Thomsen, shipwreck savant and maritime archeologist for the Wisconsin Historical Society. “They were going to give them free passage to see their family for the holidays.”

There were many such ships that transported trees—the state’s old-growth forests were gobbled up almost entirely—but in the three short years the Rouse Simmons was operating, it had become beloved. Captain Santa not only gave away many trees to families who could not afford their own, he also understood marketing, making his arrival into the Port of Chicago a large and festive affair. “They would hoist garland and leaves around the mast and rigging and string lights around the vessel,” says Thomsen. And on the top of the mast sat a Christmas tree, their own topper. “Who wouldn’t want to buy a tree from them?”

That November the Rouse Simmons was on its way to the Windy City, stocked to the brim and smelling of pine. Then, without much warning, a sudden gale blew through. Waves were violent, and choppy. The boat cut close to the shoreline, in view of a lifesaving station, staff noting in their logbook various signs of distress. When lifeguards made it down to the water, the Rouse Simmons had disappeared, tragically taking all aboard with it.

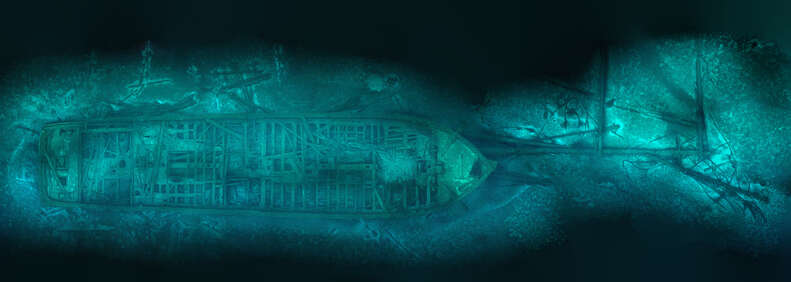

But the boat still lives, in one sense. You can find it 155 feet below the surface of Lake Michigan, part of a 962-square-mile area recently designated the Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary.

“It’s depth is at the extreme edge,” says Thomsen. “Recreational diving is down to 130 feet, but it’s very easy for beginner technical divers to see this shipwreck.” Inside the hull of the ship are Christmas trees, stacked. “Some of them still have the needles on them.”

There are over 700 ships lost to Wisconsin waters, 115 of which Thomsen and her team have examined. 36 are known to be in the Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary, but research suggests 60 or so more have yet to be rediscovered. Beyond the sheer numbers, the area is uniquely poised for preservation: the cold, dark waters have low levels of oxygen, helping to preserve wood. And unlike the ocean, the lack of salt keeps metals from corroding. The Wisconsin Historical Society is a leader in shipwreck research, maintaining an online resource for wrecks at wisconsinshipwrecks.org, and also publishing a book, Stories from the Wreckage: A Great Lakes Maritime History Inspired by Shipwrecks.

Like the Christmas Tree Ship, each wreck tells a story of the region’s—and the country’s—maritime past, beginning with Wisconsin’s position at the forefront of the Western frontier. “This was a mega highway,” says Thomsen. “Before there were roads and trains, that was the way to get people immigrating into this region.” Later, the lakes became a shipping thoroughfare, with over a thousand boats a year sailing up and down Lake Michigan in the late 1800s. As the plethora of wrecks would suggest, the traffic sometimes caused collisions. Says Thomsen: “This was also an era where very few lighthouses and little navigation existed.”

Besides weather and traffic, shipwrecks happened as a result of boiler explosions or just plain unwieldiness—like in the case of the Gallinipper, Wisconsin’s oldest shipwreck, built in 1833 for fur trader and prestigious local Michael Dousman. (You may have come across the town of Dousman, just west of Milwaukee, or one of many Dousman streets like in Green Bay.) When the fur business picked up, they cut the ship, then called the Nancy Dousman, and lengthened it. The hasty adjustment threw off its balance, and on a sail without cargo in 1851, it capsized in a surprise gust, sinking some 230 feet. Luckily, everyone made it to shore on lifeboats. “It has a mast still standing on it, which is so cool,” notes Thomsen. “Everything on that ship is hand-hewn. You can tell that it’s very old.”

And then there’s the stuff of nightmares, or at least Indiana Jones movies. Surrounding Rawley Point, just north of Two Rivers, is a treacherous patch of quicksand. “It’s kind of a trap,” says Thomsen. “Rawley Point sticks way out and [boats] get a little too close.” Once around the bend, they get stuck in the sand and sink. “I think we’ve listed eight shipwrecks on the National Register that have been lost on Rawley Point,” says Thomsen. “[With currents] they become unburied from the sand and we’ll have to run up there and look at them while they’re free. And when the next storm comes through, they’re buried again. There’s whole ships that are buried in the sand!”

It’s the job of Thomsen and Caitlin Zant, two maritime archeologists with the Wisconsin Historical Society, to chronicle these preserved pieces of cultural history. Thomsen is Midwest-modest about accolades—she was instrumental in the Shipwreck Coast gaining its protective status, has received awards from the Association for Great Lakes Maritime History and the Great Lakes Shipwreck Preservation Society, and in 2014, was inducted into the Women Divers Hall of Fame.

She’s worked on imaging the remains of the Titanic and just this November was on the Wisconsin team that unearthed a 1,200-year-old dugout canoe (a monumental discovery stumbled upon on her day off). She mostly works on shipwrecks, though she’s currently excavating an inundated iron mine in the Baraboo Range which she is particularly enthusiastic about. “There’s a wooden tool box full of tools that’s sitting on top of one of the pumps. Whoever was trying to fix the pump couldn’t, so then it was ‘run for your lives!’”

With shipwrecks, the job is to document, using data and measurements, creating a metaphorical snapshot of the site. Says Thomsen: “We have everything that someone’s been carrying on this ship: their personal effects, cargo representative of the time, and the industries that were going on at that time, too.” They construct a scaled drawing of the time capsule on the bottom of the ocean, cataloging and photographing any artifacts, leaving all the pieces in place. (If you come across a wreck in the sanctuary, take note that it’s illegal to remove anything.) “We leave everything, not just so it’s new to us, but it’s new for every person that comes behind us,” says Thomsen. “People that dive here, they wanna see the stuff. That’s why they come.”

Thanks to the efforts of Thomsen and her team, 27 of the shipwrecks in Wisconsin’s waters are on the National Historic Register—each taking a thesis-load amount of work, some with 45 pages of historical record alone. Fortunately, the area’s recent designation as a maritime sanctuary has led to greater resources: in addition to extra funding, it protects all the shipwrecks at a federal level from looting or damage.

Quite a few of the shipwrecks are accessible for the adventurous. The Gallinipper and the Christmas Tree Ship can be reached by diving; so too can the Vernon, an elegant freight and passenger steamer that went down in 1887 just one year after being built; and Home, an 1850s trading vessel suspected to have played a part in the Underground Railroad. Sinking in a schooner collision, it now sits upright underwater. “It’s an absolutely beautiful shipwreck,” says Thomsen. “You can still see the damage starboard-side where the William Fiske hit.”

You can kayak or snorkel up to the Arctic, an 1881 icebreaking tugboat that sank in 1930, now under 14 feet of water. But you’ll need an ROV (remotely operated vehicle) to see inside Thomsen’s favorite wreck in the sanctuary: the Senator, which met its demise in October of 1929 carrying 268 Wisconsin-made Nash automobiles. The wreck sits 450 feet below the surface, with some pristine throwback—and very cool-looking—cargo still intact. “If you think about it, that’s two days after the market crashed,” says Thomsen. “So they had all this stock and they were going to try to take it to market and get what they could. And then they lost all of their vehicles. This company amazingly survived the whole Depression after that loss.”

For above-water deep dives into Wisconsin maritime history, there are several maritime museums to explore, including the Villa Louis Historic Site, an 1870s Victorian mansion built by the Dousman family, and the Wisconsin Maritime Museum, 60,000 square feet dedicated to the waterways of the Great Lakes region, with model ships, an operating steam engine, and submarines like the WWII-era USS Cobia.

Or just grab a wetsuit and go exploring on your own. Just watch out for quicksand.